Elevated levels of lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a), are increasingly recognized as one of the most powerful and independent risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Lp(a) is not just another cholesterol particle. It has unique properties that can significantly increase the risk of arterial narrowing, blood clots, and heart valve calcification. Even people with a healthy cholesterol profile can develop heart problems because of it.

Why Lp(a) plays such an important role

Lp(a) closely resembles regular LDL cholesterol but contains an extra protein component called apolipoprotein(a), which changes its behavior. As a result, Lp(a) combines the disadvantages of both worlds — it can accumulate in the arteries and also influence inflammation and blood clotting.

How elevated Lp(a) damages the heart and blood vessels:

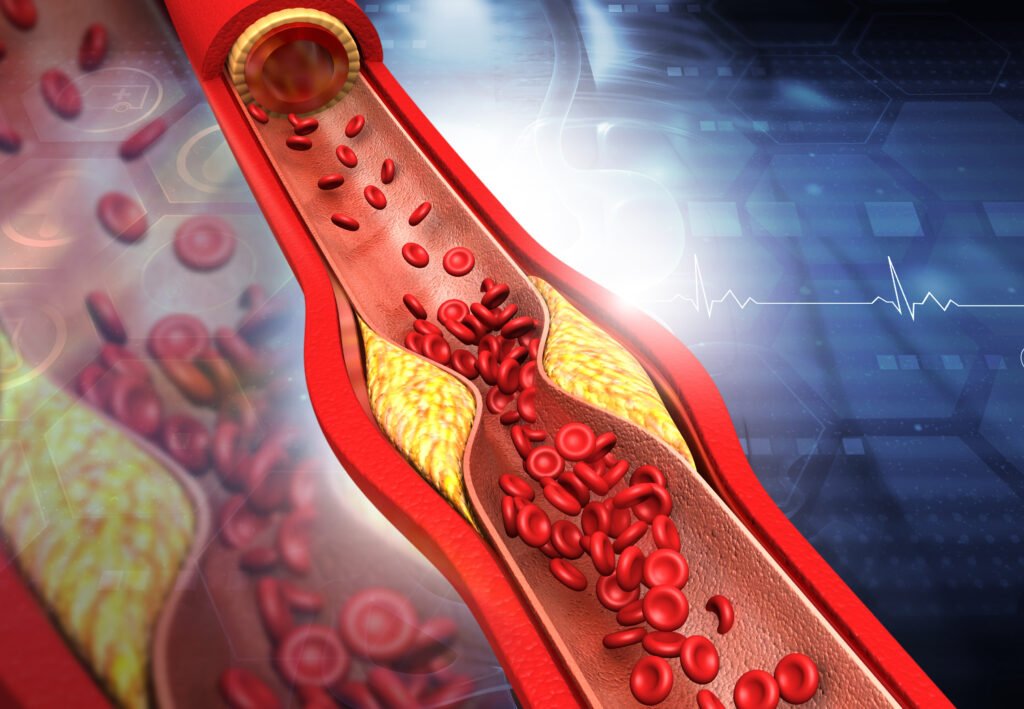

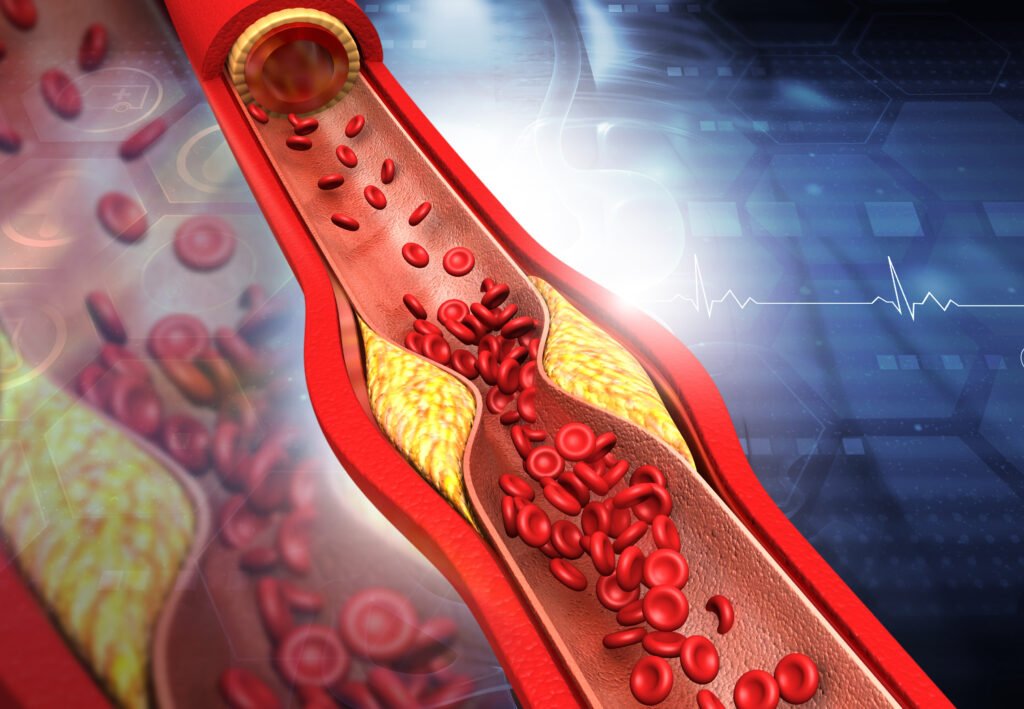

1. Cholesterol build-up in the arterial wall – Lp(a) penetrates the walls of blood vessels and sticks there. This causes atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), which makes blood vessels narrower and reduces blood flow.

2. Inflammation of the arterial wall – The accumulation of Lp(a) triggers inflammatory reactions. This can make fatty deposits in the vessel wall (“plaques”) fragile and unstable. If such a plaque ruptures, a blood clot can suddenly form, potentially leading to a heart attack or stroke.

3. Reduced breakdown of blood clots – Lp(a) closely resembles a protein that normally helps dissolve blood clots. Because of this similarity, it disrupts that natural process — causing clots to persist longer and increasing the risk of arterial blockages.

That is why Lp(a) is not just a silent risk factor, but an active cause of cardiovascular disease — even in people with an otherwise healthy cholesterol profile.

Lp(a) and heart attack

A high Lp(a) level increases the risk of coronary heart disease, even in people with normal LDL cholesterol levels. Research shows that among patients under the age of 60 who experience a heart attack, more than one in three have elevated Lp(a) levels.

How this happens:

- Lp(a) attaches itself to damaged vessel walls in the coronary arteries.

- It promotes plaque formation and inflammation.

- It inhibits the natural breakdown of blood clots, making arterial blockages more likely.

Even slight elevations in Lp(a) can contribute to a higher long-term risk of heart attacks, especially when combined with smoking, high blood pressure, or diabetes.

Lp(a) and stroke

In addition to heart attacks, Lp(a) also plays a role in strokes (TIA or ischemic stroke). Studies show that high Lp(a) levels are associated with an increased risk of ischemic stroke, particularly in people under the age of 65.

Mechanism:

- Lp(a) promotes inflammation and clot formation in the arteries of the brain.

- It increases the likelihood of arterial calcification in the carotid arteries.

- It can lead to small blood clots that block blood flow to brain tissue.

Although strokes have multiple causes, an elevated Lp(a) level can double the risk, even when other risk factors are well controlled.

Lp(a) and aortic valve stenosis

One of the most well-established connections is between Lp(a) and aortic valve calcification (aortic valve stenosis).

The apolipoprotein(a) component of Lp(a) promotes the deposition of fats and calcium on the heart valves. Over time, this causes the aortic valve to become stiffer and thicker, forcing the heart to pump harder to push blood through.

Key facts:

- Lp(a) is currently the only known genetic risk factor for aortic valve stenosis.

- People with high Lp(a) levels are two to three times more likely to develop this condition than those with low levels.

- In practice, valve calcification often starts five to ten years earlier and progresses faster, especially from middle age onward.

The disease usually develops slowly and without clear symptoms at first. Over time, however, the valve can become so rigid that the heart struggles to circulate blood properly — with shortness of breath, chest pain, or fatigue as early warning signs.

Because there are currently no medications that can stop valve calcification, early detection of Lp(a) is especially important for people with a family history of heart valve disease.

Early atherosclerosis: how Lp(a) causes damage

Atherosclerosis (hardening of the arteries) is the underlying process behind most cardiovascular diseases.

In people with elevated Lp(a) levels, this process often begins earlier in life.

How Lp(a) damages the arterial wall:

- It binds to damaged vessel tissue and deposits cholesterol within the wall.

- It contains pro-inflammatory substances that make plaques unstable.

- It slows the breakdown of blood clots, allowing blockages to form more easily.

- It carries oxidized phospholipids, which accelerate vascular aging.

As a result, arteries in people with high Lp(a) levels can already show signs of narrowing at a much younger age.

Clinical relevance: why measuring matters

The link between Lp(a) and cardiovascular disease is now so strong that international guidelines recommend that every adult should have their Lp(a) measured at least once in their lifetime.

An elevated Lp(a) level helps to better assess your personal cardiovascular risk and to take timely action when needed.

Key steps include:

- Starting early and intensive LDL-lowering treatment.

- Maintaining stricter control of blood pressure and blood sugar.

- Paying more attention to lifestyle, physical activity, and quality sleep.

- Increasing awareness within families where heart problems are common.

Measuring Lp(a) is not a luxury, but an essential part of modern cardiovascular prevention.

Sources

Scientific sources and medical references. The information on this page about lipoprotein(a) as an independent risk factor for myocardial infarction, stroke, aortic valve stenosis, and atherosclerosis is based on the following scientific publications:

Nordestgaard BG, Chapman MJ, Ray K, et al.

Lipoprotein(a) as a cardiovascular risk factor: current status.

European Heart Journal, 2010.

Comprehensive landmark review establishing lipoprotein(a) as an independent, genetically determined cardiovascular risk factor and summarizing epidemiology, biology, and clinical relevance.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20965889/

Kamstrup PR, Benn M, Tybjærg-Hansen A, Nordestgaard BG.

Extreme lipoprotein(a) levels and risk of myocardial infarction in the general population: the Copenhagen City Heart Study.

Circulation, 2008.

Large population-based study demonstrating a strong, dose-dependent association between very high Lp(a) levels and the risk of myocardial infarction in the general population.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18086931/

Burgess S, Ference BA, Staley JR, et al.

Association of LPA variants with risk of coronary disease and aortic valve stenosis.

JAMA Cardiology, 2018.

Mendelian randomization study providing causal evidence that genetically elevated Lp(a) increases the risk of coronary artery disease and calcific aortic valve stenosis.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/29926099/

Van der Valk FM, Bekkering S, Kroon J, et al.

Oxidized phospholipids on lipoprotein(a) elicit arterial wall inflammation and an inflammatory monocyte response in humans.

Circulation, 2016.

Mechanistic human study showing that oxidized phospholipids carried by Lp(a) directly trigger vascular inflammation, explaining its role in atherosclerosis.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27496857/

Kronenberg F, Mora S, Stroes ESG, et al.

Lipoprotein(a) in atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease and aortic stenosis: A European Atherosclerosis Society consensus statement.

European Heart Journal, 2022.

Authoritative European consensus statement summarizing evidence on genetics, pathophysiology, screening recommendations, and clinical management of elevated Lp(a).

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36036785/

NL - Nederlands

NL - Nederlands EN - English

EN - English DE - Deutsch

DE - Deutsch